Text by Muhammad Azka Muharam

Pharoah Sanders possesses one of the most distinctive tenor saxophone sounds in jazz. Harmonically rich and heavy with overtones, Sanders’ sound can be as raw and abrasive as a saxophonist can produce. Yet, many jazz fans highly regard Sanders to the point of reverence. Although he made his name with expressionistic, nearly anarchic free jazz in John Coltrane’s late ensembles of the mid-’60s, Sanders’ later music is guided by more graceful concerns. The hallmarks of Sanders’ playing then were naked aggression and unrestrained passion. In the years after Coltrane’s death, however, Sanders explored other, somewhat gentler and perhaps more cerebral avenues — without, it should be added, sacrificing any of the intensity that defined his work as an apprentice to Coltrane.

Pharoah Sanders (his given name, Ferrell Sanders) was born into a musical family. Sanders’ early favorites included Harold Land, James Moody, Sonny Rollins, Charlie Parker, and John Coltrane. Known in the San Francisco Bay Area as “Little Rock,” Sanders soon began playing bebop, rhythm & blues, and free jazz with many of the region’s finest musicians, including fellow saxophonists Dewey Redman and Sonny Simmons, as well as pianist Ed Kelly and drummer Smiley Winters. In 1961, Sanders moved to New York, where he struggled. Unable to make a living with his music, Sanders pawned his horn, worked non-musical jobs, and sometimes slept on the subway. During this period, he played with several free jazz luminaries, including Sun Ra, Don Cherry, and Billy Higgins.

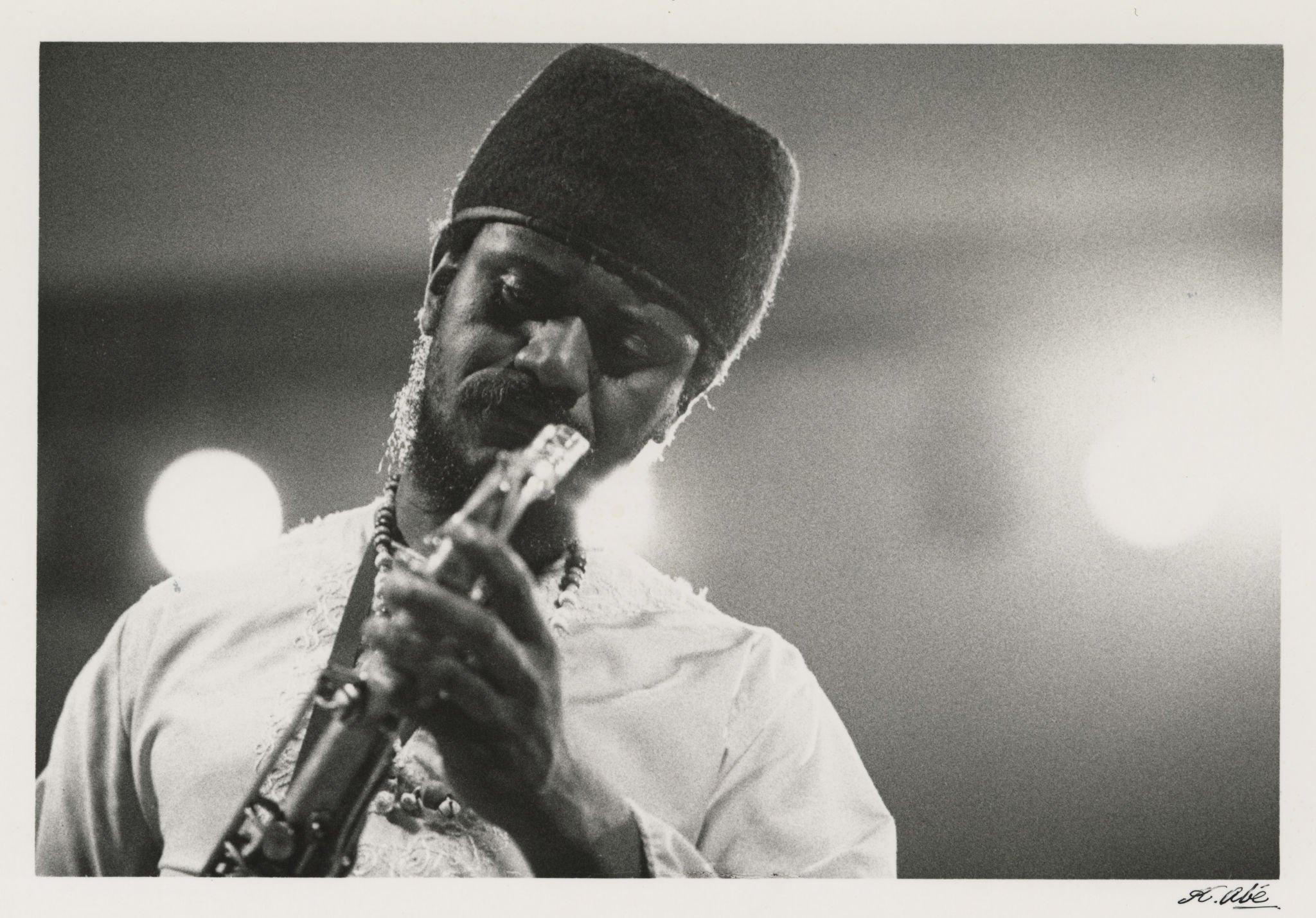

Pharoah Sanders plays tenor saxophone at Carnegie Hall, New York, United States, 1972. (Photo by K. Abe/Shinko Music/Getty Images)

THE HAGUE, NETHERLANDS – JULY 14: Pharoah Sanders, tenor saxophone, performs on July 14th 1996 at the North Sea Jazz Festival, The Hague, Netherlands. (Photo by Frans Schellekens/Redferns)

In 1964, Coltrane asked Sanders to sit in with his band. The following year, Sanders was playing regularly with the Coltrane group. Coltrane’s ensembles with Sanders were some of the most controversial in jazz history. Their music represents a near-total desertion of traditional jazz concepts, like swing and functional harmony, in favor of a teeming, irregularly structured, organic mixture of sound for sound’s sake. Strength was necessary in that band, and as Coltrane realized, Sanders had it in abundance.

Sanders made his first record as a leader in 1964. After John Coltrane died in 1967, Sanders worked briefly with his widow, Alice Coltrane. From the late ’60s, he worked primarily as a leader of his ensembles.

In the decades after his first recordings with Coltrane, Sanders developed into a more well-rounded artist, capable of playing convincingly in various contexts, from free to mainstream. Some of his best work is his most accessible. As a mature artist, Sanders discovered a hard-edged lyricism that has served him well.

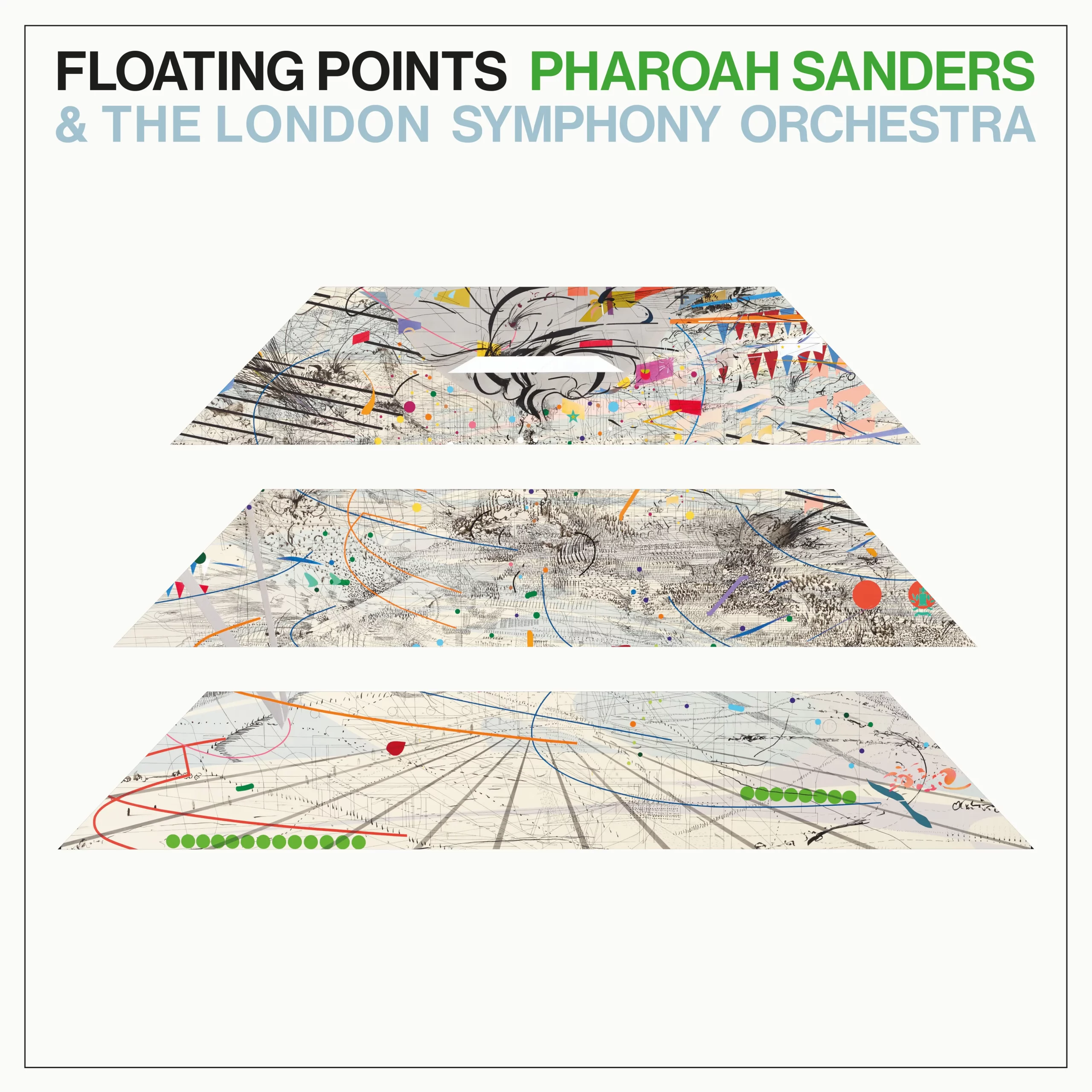

In 2020, Sanders recorded an album, Promises, with the English electronic music producer Floating Points and the London Symphony Orchestra. It was released in March 2021, Sanders’s first major new album in nearly two decades. It was widely acclaimed, with Pitchfork declaring it “a clear late-career masterpiece.”

Like so many of his generation, Sanders channeled spirit into song, drawing inspiration from a panoply of sacred sources.

For a while, younger hip-hop generations also found words and meaning in a similar kind of search. The music –along with the quest – continued.

But jazz has changed, and hip-hop has changed.

The assembly of American jazz musicians from the mid-20th century who spent their careers seeking spiritual transcendence reads like a pantheon of American genius: John Coltrane, Randy Weston, Yusef Lateef, Ahmad Jamal, Alice Coltrane, Sahib Shahab, Abbey Lincoln, Art Blakey, Sun Ra. These were players willing to take giant steps across scales and continents to find meaning in the sounds of others. They turned that sound into purpose for themselves, and they did it for decades. Central to this sometimes screeching, frequently psychedelic, and always expansive quest was the sonic travel this music took, an inspirational voyage into the mighty souls of African and Asian folks, regularly and intricately braided with, among other influences, the soundscape of Islam.