No products in the cart.

Column

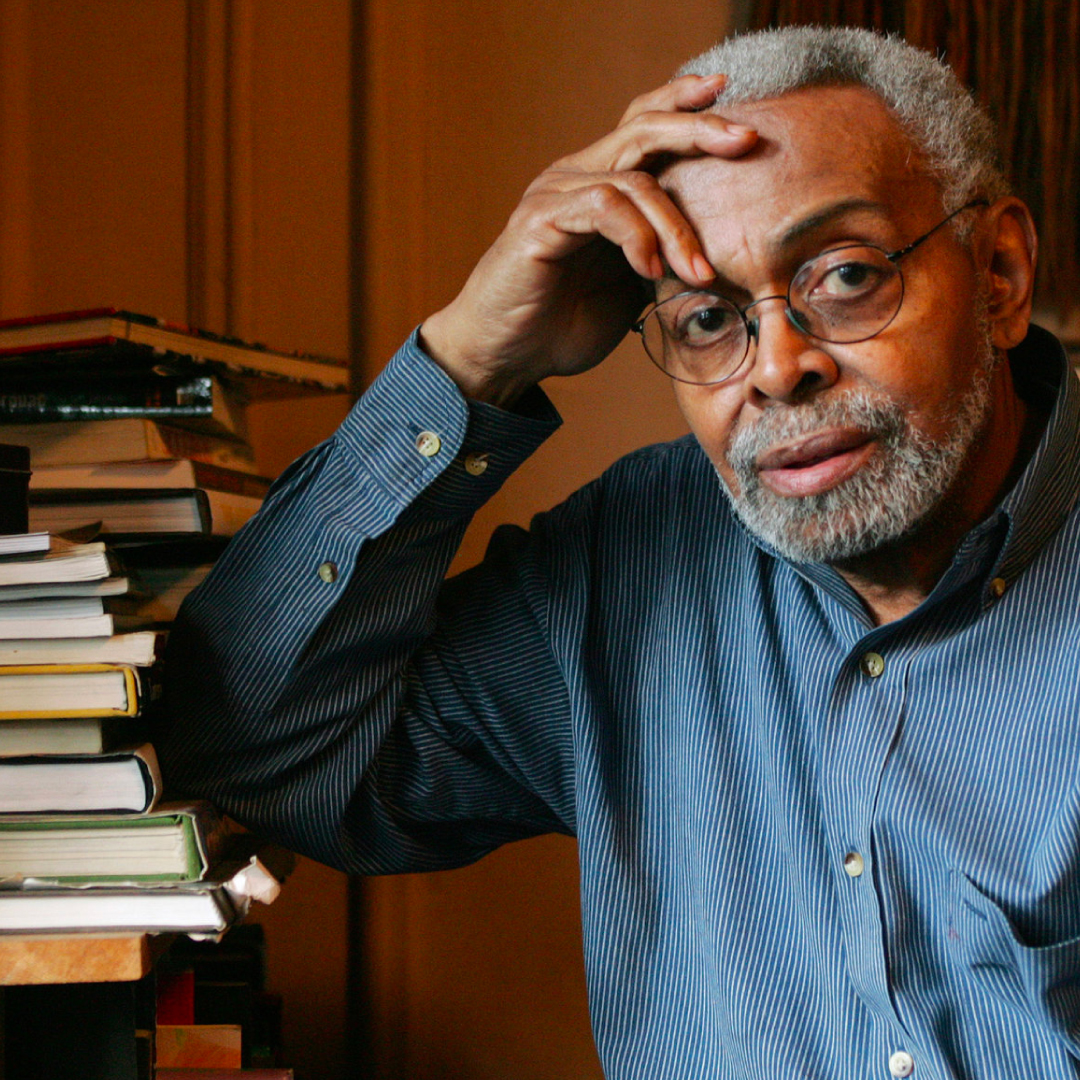

Amiri Baraka’s “Dope” – A Further Analysis

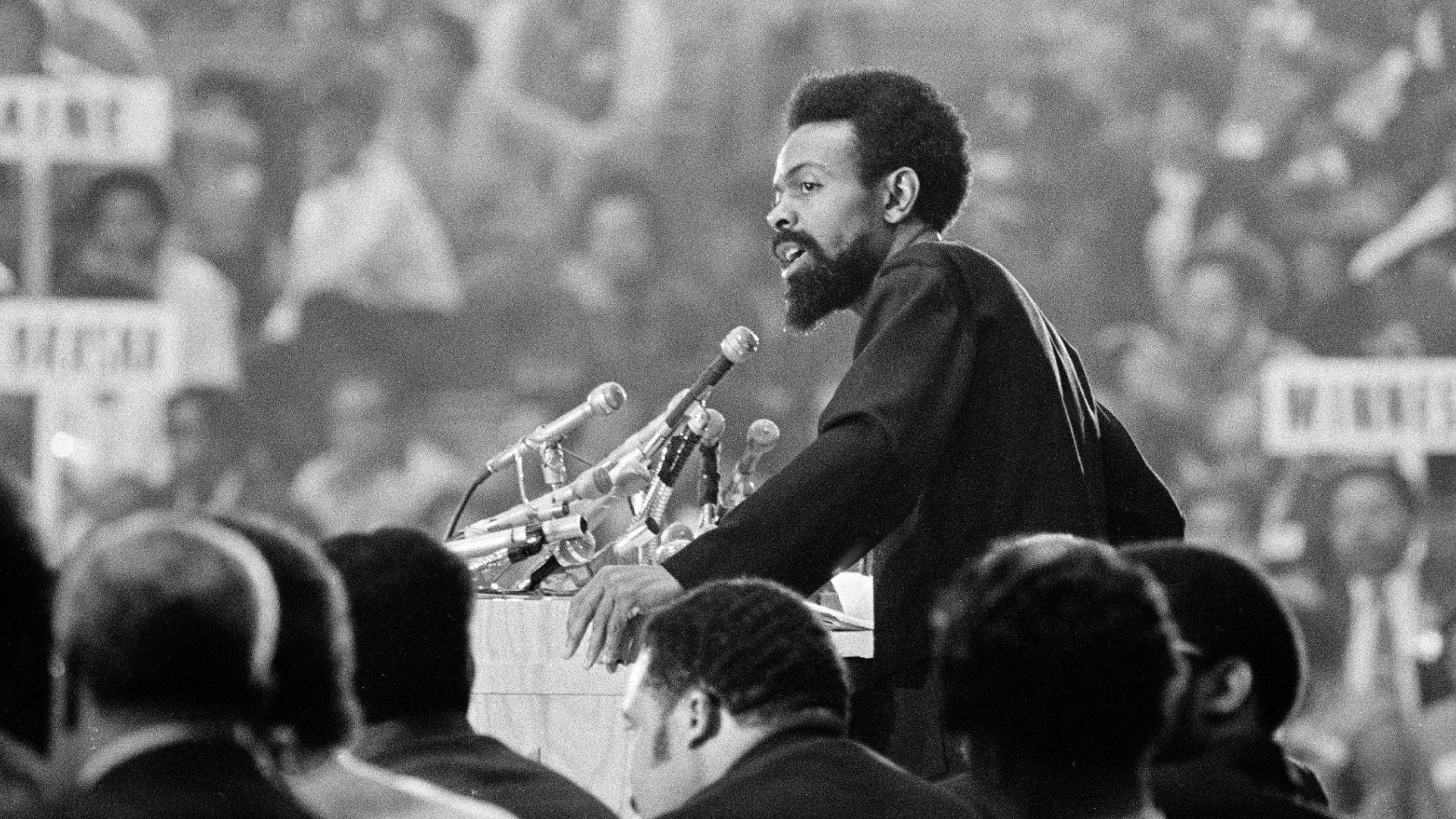

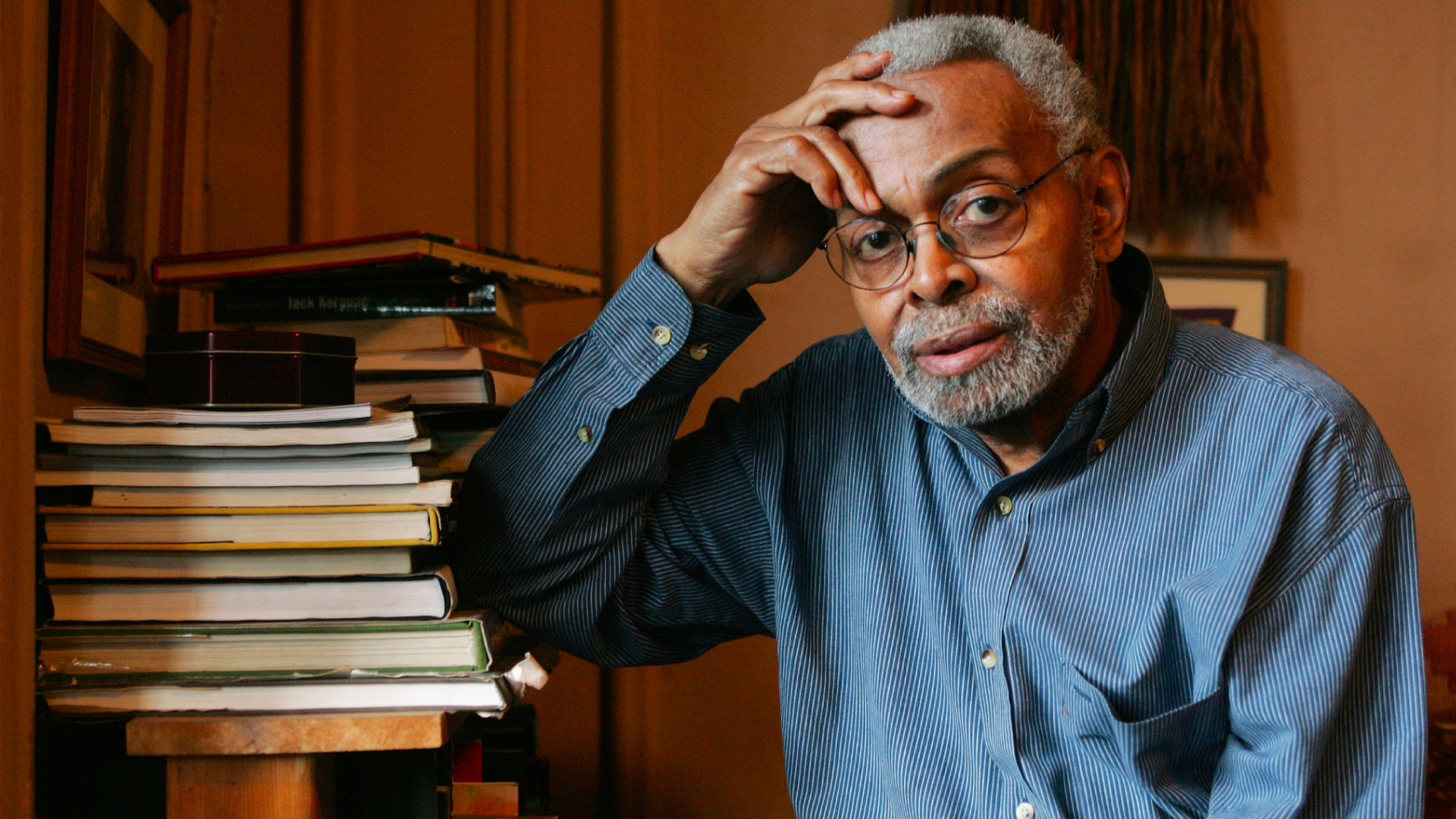

Source Photo by nytimes.com

Text by Muhammad Azka Muharam

Poetry comes in many different forms. The very basics of a poem usually comes with stanza a-b-a-b that the ending rhymes. But this poem brings out the free-form, free-verse style you have never seen and read before.

Poet, writer, teacher, and political activist Amiri Baraka was born Everett LeRoi Jones in 1934 in Newark, New Jersey. He attended Rutgers University and Howard University, spent three years in the U.S. Air Force, and returned to New York City to attend Columbia University and the New School for Social Research. Baraka was well known for his strident social criticism. He often wrote in an explosive style that made it difficult for some audiences and critics to respond objectively to his works. Throughout most of his career, his method in poetry, drama, fiction, and essays was confrontational, calculated to shock and awaken audiences to the political concerns of black Americans. For decades, Baraka was one of the most prominent voices in the realm of American literature.

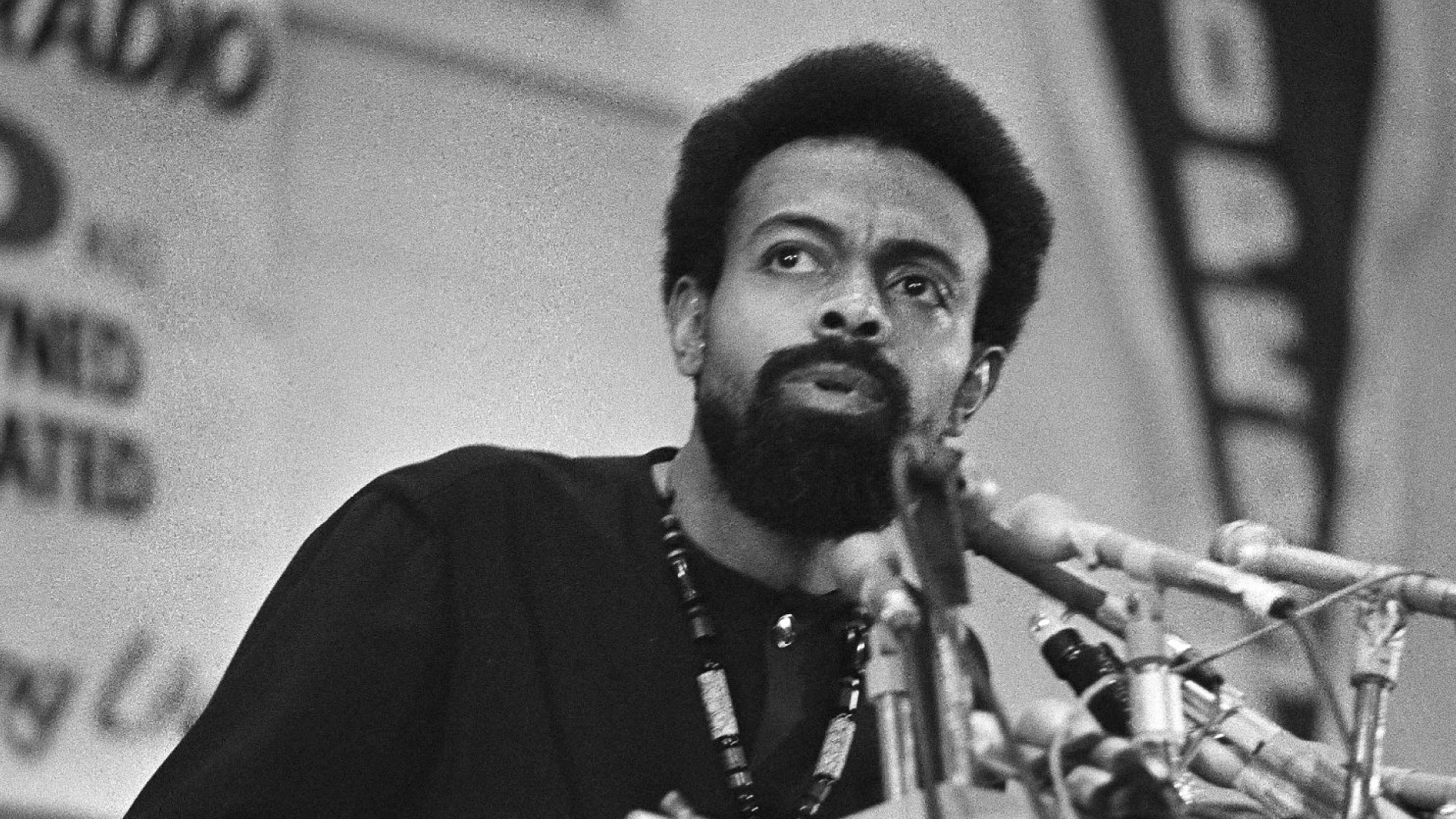

Source photo nydailynews.com

“Dope” by Amiri Barka is such a mind-blowing masterpiece. This spectacular, searing, satirical, and humorous piece has Baraka taking on the persona of a black preacher giving a passionate sermon (really, it’s a parody of a sermon). As the speaker convinces his audience (high) that all the problems black people have faced throughout history are due to the devil. He convinces them that it must be the devil responsible.

“lazy niggers chained theyselves and threw they own black asses in the bottom of the boats,” announces the preacher of Baraka’s poem.

To fully appreciate Baraka’s abilities as a reader, writer, and performer, it is necessary to hear and read the poem.

This poem launches not with formal poetic language but with grunting vowels, specifically the letter “u” which is interesting because he’s talking to us, to “you,” but it’s unintelligible and, frankly, sounds like the animal noises we’d expect “rockefeller” would hear instead of a human being addressing another human being. It has a tribal quality and goes on and on to get our attention, but it has a musical quality, like some dark African black chant. Also, there is a funny bit of intertextuality here that I’m not sure if it’s intended or not, but in the sitcom “Welcome Back Kotter” Horshack would make the same sound when trying to get Kotter’s attention in class.

And while I don’t want to write about every line in the poem (though I probably could), other things that stand out for me are his use of stage directions. He writes “(Screams)” but doesn’t say “(Screams).” Instead, he screams the next line, “ooowow! ooowow! It must be / the devil”. He follows in another direction “(jumps up like a claw stuck him) oooo / wow! Oooowow!”. So when we read this as opposed to listening to it, we are, in a way, getting something like what Shakespeare would be doing in giving the actor direction in the play, only here Baraka is telling us (telling “u”) how to act. In a way, he transcends a traditional form of plays and direction to give direction to an audience that needs to act.

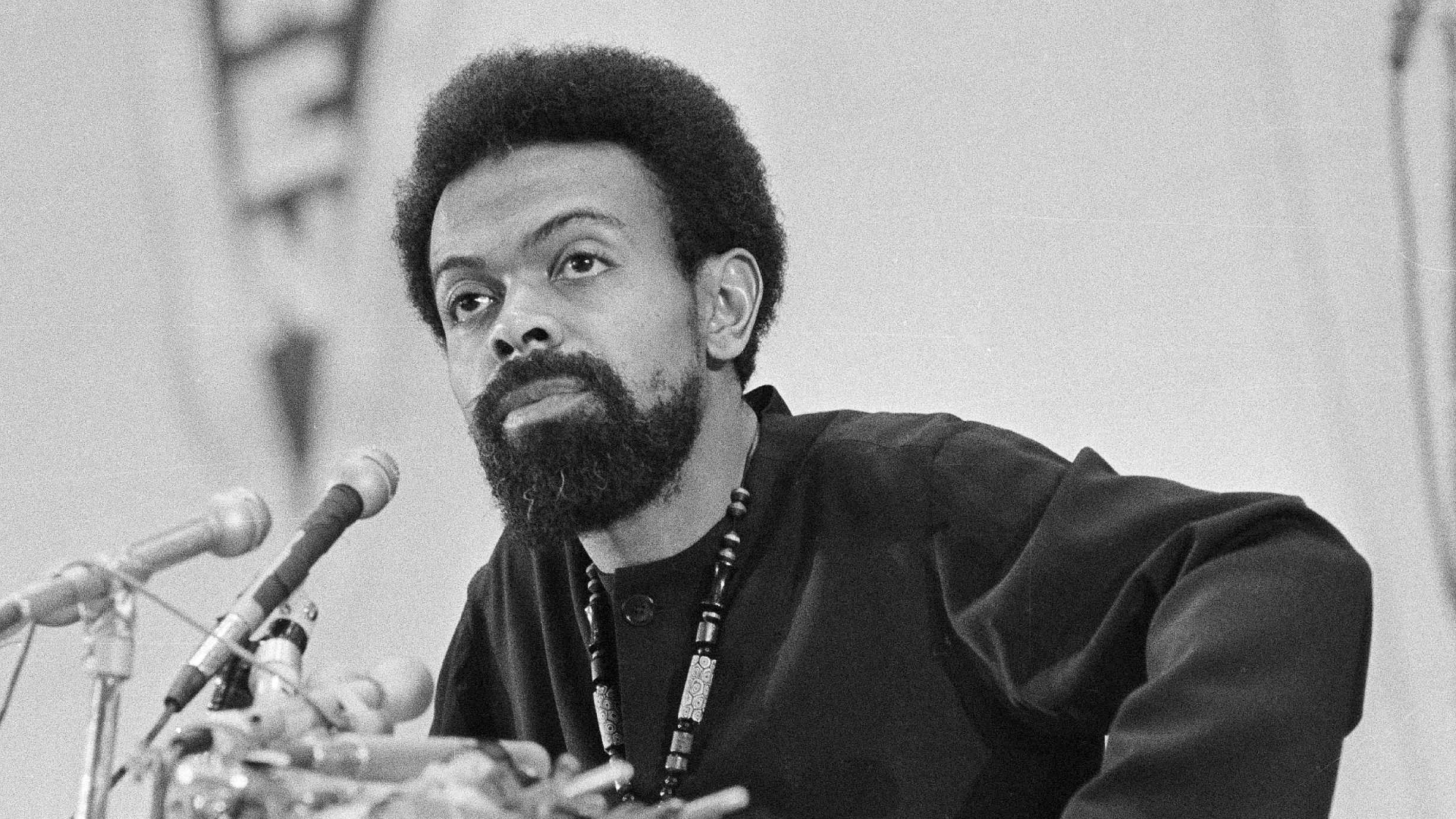

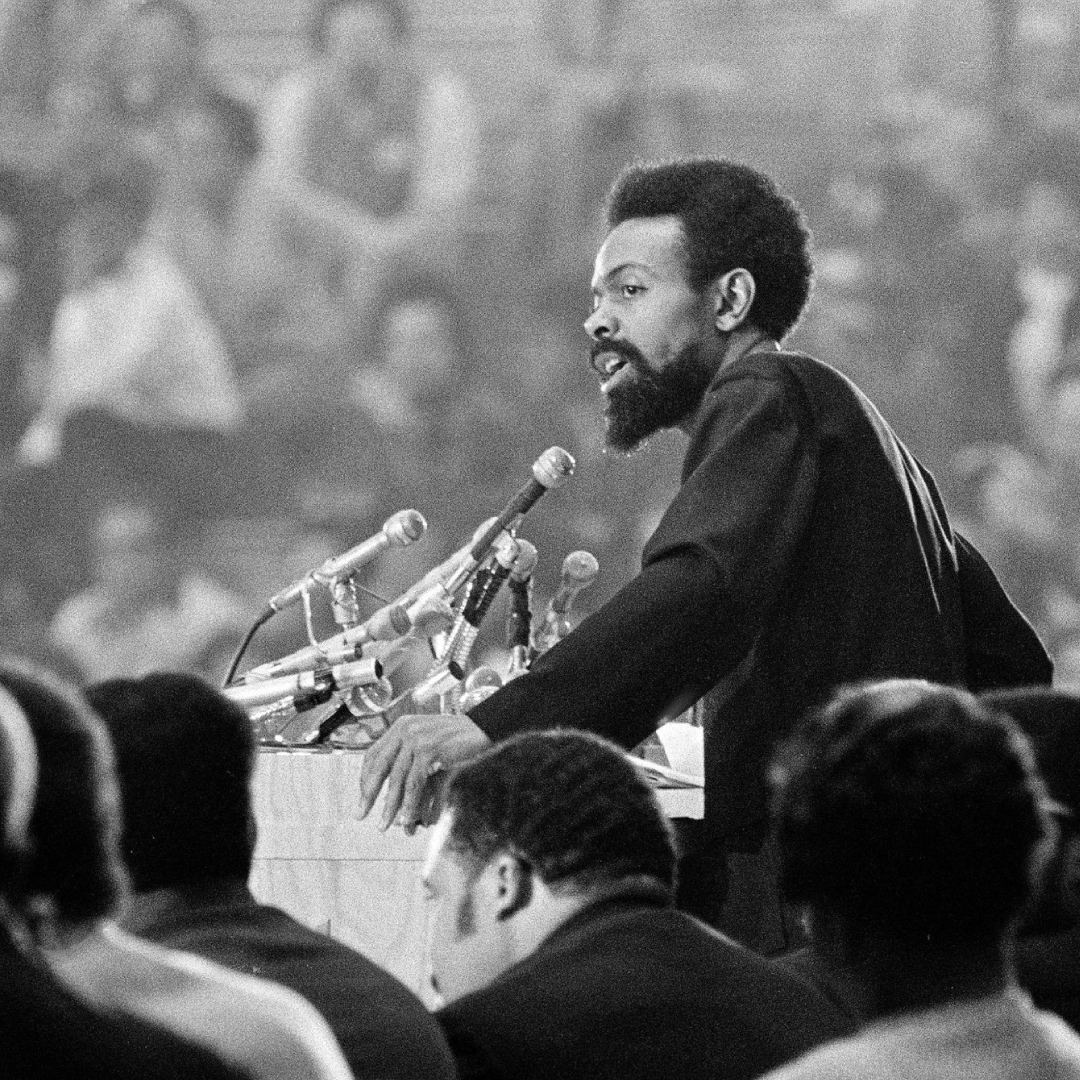

Source photo nytimes.com

And the role he plays feels very much like that of the preacher. Yet, it’s an odd preacher who could also be a drug addict (the poem’s called “Dope” after all), so he’s embodying many roles of the black man in his poem. He’s a one-man show.

But this isn’t just performativity masking a poem that needs to work. This is a powerful work all on its own, specifically in the lines “going to heaven after i / die, after we die / everything going to be different, after we die. “This line, “after we die,” sums up so much about the attitudes towards African Americans (whites wish they would die). That African Americans have of themselves in that there’s a sort of cynicism that the world isn’t for them and that hope can only be found in death, but that’s coupled with a weird savior mentality in that they will find glory in death. Still, this Jesus savior mentality is mixed up with African and Muslim religion that rejects (through the implied sarcasm) the hegemonic institutions of Western Religion.

“after we die” might actually be the most powerful line of poetry written in the 20th century. That sarcasm permeates this whole poem, especially with his sarcastic apology for Jimmy Carter as being a friend to black people even though “nixon lied, haldeman lied, dean lied, hoover / lied hoover sucked (dicks) too” – (dicks) not being performed but left as a gift just for readers – and with “drunken racist brother ain’t no reflection” which is about Carter’s actual brother and together it’s an indictment of all white people in power as a group that can’t be trusted. And this also implicates the entire left because just because the left finally got one of their “own” in the White House (Carter), nothing is really gonna change – at least until “after we die”.

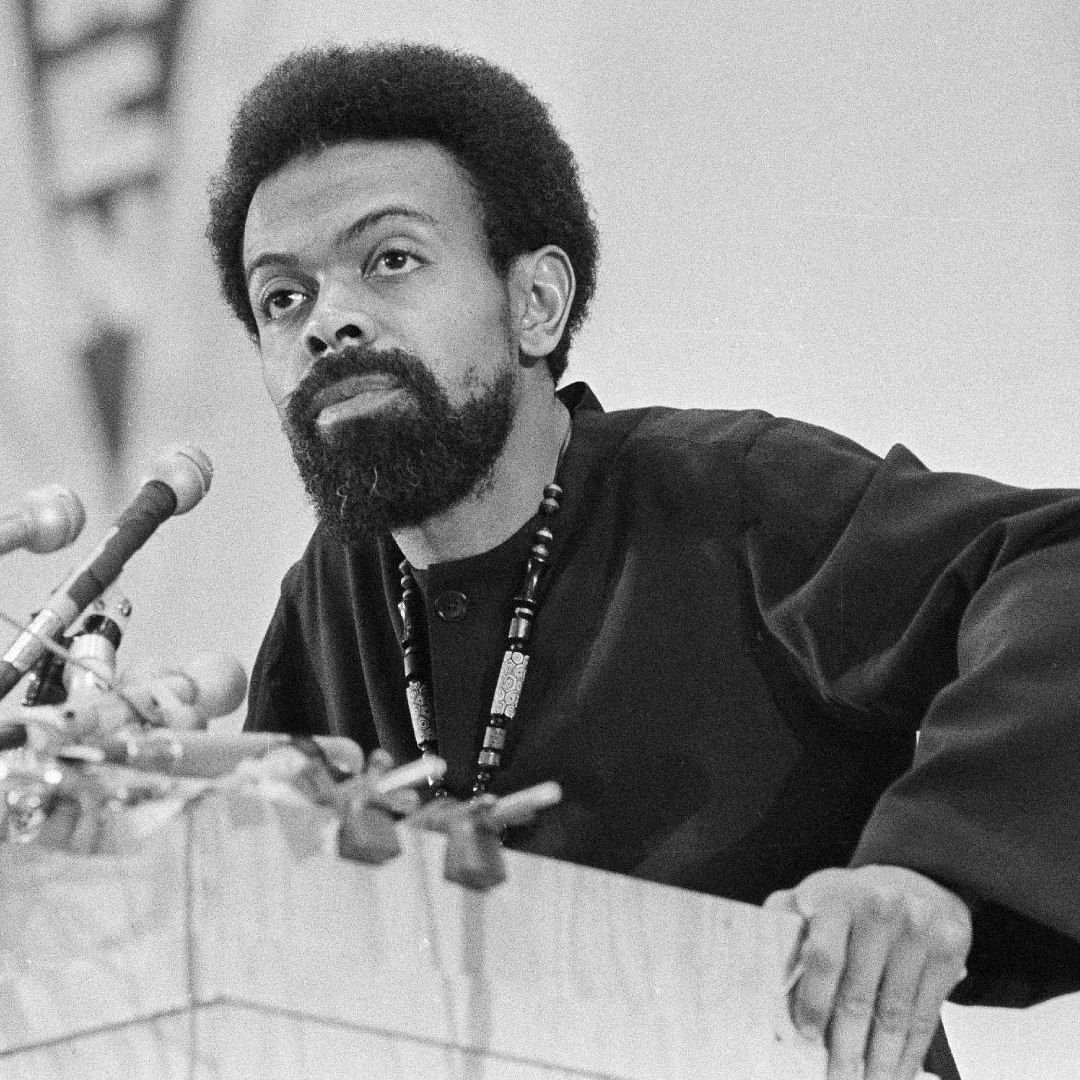

Source Photo thenation.com

His sarcasm doesn’t end with white people, though. He also indicts black culture for buying into a religion that wants your money, “gimme / that last bitta silver you got” and with his tone of soothing the audience with “o back to work and lay back” and “now go back to work, go to sleep, yes,” for buying into a rigged system that doesn’t give a fuck about them. At all.

This poem is dope. Literally. It’s the dope (dupe) that has been fed to black people since “Assblackuwasi helped throw yr ass in / the bottom of the boat”, it’s the dope that tricks you into thinking another white man in the white house will do you a solid, it’s the dope that religion has fed black people into giving up their lives right now for a better life in heaven so the white man can live good now. It’s dope, alright. And the way he ends it with the same “u”, but this time he sounds like he’s weeping. And he weeps because he’s tired and sad and fed up.